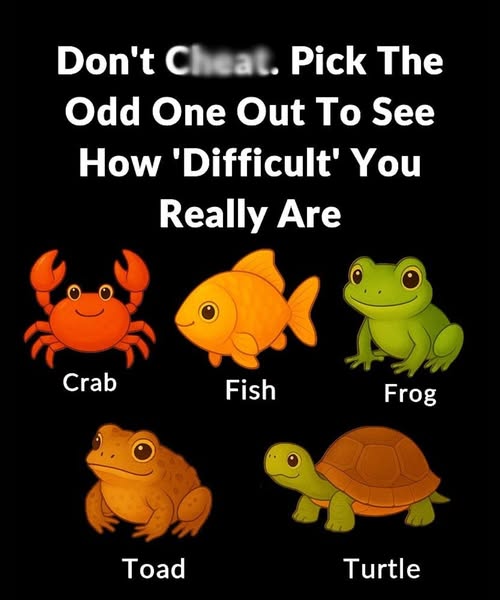

Another group chooses the fish. They glance at the list, ignore the visual details, and immediately think about environment. Four of the animals can survive outside the water for at least part of their lives. One cannot. The fish is fully aquatic, and that fact dominates the decision for people who think in terms of setting, surroundings, and context. These are the thinkers who notice where things belong, who they belong with, and how their world fits together. They’re sensitive to ecosystems, relationships, and the rules of environments. They tend to categorize based on function and habitat rather than looks.

Some puzzle-takers point to the frog with surprising confidence. Their reasoning has nothing to do with looks or habitat. Instead, they’re thinking about development and transformation. Frogs begin life as tadpoles, with gills and tails, then undergo a dramatic metamorphosis into adults. While other animals also have life stages, none of them transform in quite the same way. People who choose the frog often appreciate process, evolution, and the path an organism takes to become what it ultimately is. They are drawn to stories of change and growth. They notice journeys more than static traits. For them, the odd one out is the creature whose life simply isn’t straightforward.

Then there are the people who pick the toad. These individuals look at the frog and toad side by side and immediately start comparing the subtle differences: the drier, bumpier skin of the toad, its preference for land over water, its slightly different build. Many casual observers lump frog and toad together, but those who choose the toad usually have sharp eyes for nuance. They pick up on texture, behavior, and details that others might gloss over. This choice reveals a mind that values subtlety, that notices details the average person misses, and that enjoys distinguishing things that most people consider nearly identical.

And of course, there are those who confidently point to the turtle. Their logic is rooted in taxonomy and classification. The turtle is a reptile; the frog and toad are amphibians; the fish is, well, a fish; the crab is a crustacean. For people with this perspective, the odd one out isn’t about appearance, environment, or life cycle—it’s about biological categories. The turtle stands alone as the only reptile, and that unmistakable difference becomes the deciding factor. These individuals gravitate toward systems, structures, and scientific groupings. They think in terms of definitions, categories, and the larger frameworks that organize knowledge.

What makes this puzzle fascinating is that every single answer is valid depending on the angle from which a person approaches the comparison. The crab is visually unique. The fish is environmentally unique. The frog is developmentally unique. The toad is behaviorally unique. The turtle is taxonomically unique. Five animals, five different ways to separate one from the group, and each method reveals a different style of thinking.

Some people latch onto the first striking detail. Others look deeper. Some prefer logic, some focus on biology, and some rely on instincts they can’t quite explain. The puzzle works because it’s simple enough to draw anyone in but open enough to reveal subtle personality cues. It shows whether you rely on visual processing, contextual analysis, scientific classification, or detail-oriented observation.

It also reveals something else: humans don’t all prioritize the same information when they approach a problem. Some people start with what’s obvious; others immediately search for hidden layers. Some rely on what they’ve learned; others rely on what they see. That variety is what makes the world interesting.

When you ask a group of people to choose the odd one out and explain why, you see just how differently our minds are wired. One puzzle, endless interpretations. And none of them wrong.

That’s the quiet brilliance of this exercise. It doesn’t measure intelligence or knowledge. It measures perspective. It highlights the many ways humans make sense of the same set of facts. And it reminds us that even when we’re looking at the same five animals, we’re not always seeing the same thing.

These puzzles work not because they challenge the eyes, but because they reveal the mind behind the eyes — the instincts, the priorities, the habits of thought that shape how we interpret the world. And sometimes, by choosing the odd one out, we end up discovering something unexpected about ourselves.