Figures such as former Senate Majority Leader George Mitchell, former New Mexico Governor Bill Richardson, former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak, and others occupy this uneasy middle ground. Their names have surfaced in various contexts related to Epstein, yet none has been convicted or formally charged in connection with his crimes. Some have issued categorical denials. Others have acknowledged limited contact while rejecting any suggestion of wrongdoing. Legally, they remain unproven. Publicly, they remain under a cloud.

Dershowitz’s own history illustrates how destructive that ambiguity can be. He was directly accused by Virginia Giuffre, one of Epstein’s most well-known accusers, who claimed he had engaged in sexual misconduct. After years of litigation and public scrutiny, Giuffre formally withdrew her allegations against him. No court ever found Dershowitz liable. The accusation collapsed—but not before inflicting immense personal and professional damage.

That episode alone serves as a cautionary tale about the power of accusation in an era of instant information and permanent digital records. Even when claims are retracted, the initial allegation often remains more visible than the correction. Search engines, social media algorithms, and partisan commentary do not easily forget.

Another example underscores the risk even more starkly. Sarah Ransome, an Epstein accuser, later admitted that she fabricated some of her most explosive allegations. She acknowledged that claims involving figures such as Bill Clinton, Donald Trump, and Richard Branson were not true. Yet those statements, despite being admitted falsehoods, remain embedded in legal filings, media archives, and online databases. They continue to resurface, stripped of context, as if confession never occurred.

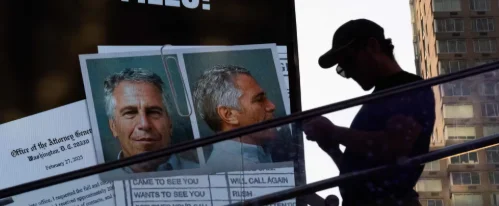

This is the paradox at the heart of the Epstein files. On one hand, there is a legitimate and urgent demand for transparency. Epstein’s crimes were real, systematic, and protected for years by wealth, influence, and institutional failure. Victims deserve justice, and the public has a right to know who enabled, ignored, or participated in abuse. On the other hand, releasing unfiltered material—especially allegations never tested in court—risks destroying innocent lives alongside guilty ones.

That tension has intensified with renewed calls to unseal Epstein-related documents. A presidential order directing federal agencies to review and potentially release additional files has added urgency to the debate. Supporters argue that sunlight is the only way to dismantle elite impunity. Critics warn that mass disclosure without careful vetting could weaponize unproven claims and turn due process into collateral damage.

Legal experts emphasize that investigative files are not verdicts. FBI interviews, victim statements, and affidavits often include uncorroborated information gathered precisely so investigators can sort fact from fiction. When those materials are released without context, the public may interpret inclusion as guilt, even when the justice system never reached that conclusion.

The political implications are enormous. In a polarized environment where accusations are readily used as weapons, selective leaks or misleading narratives can shape elections, careers, and public trust. High-profile names—especially those associated with power, wealth, or influence—become symbols rather than individuals, judged not by evidence but by proximity.

Dershowitz’s warning is not a defense of secrecy for its own sake. It is a reminder that truth-seeking requires discipline, not just exposure. Transparency without precision can become another form of injustice. The Epstein case has already demonstrated how institutions failed victims for years; repeating that failure by abandoning standards of proof would only compound the harm.

There is also a deeper cultural question at play. Can a society conditioned by outrage cycles, click-driven media, and algorithmic amplification handle nuance? Can it distinguish between accusation and adjudication, between being named and being proven guilty? Or has the very concept of due process become too slow, too restrained, for a digital age that demands instant moral clarity?

For victims, the stakes are equally high. Some fear that reckless disclosure could discredit legitimate claims by mixing them with admitted falsehoods. Others worry that continued secrecy protects powerful abusers. Both concerns are valid, and neither is easily resolved.

What emerges from the Epstein saga is not a simple battle between exposure and cover-up, but a test of whether democratic institutions—and the public itself—can uphold justice without surrendering to spectacle. Accountability must be real, evidence-based, and fair. Anything less risks replacing one kind of abuse with another.

As Epstein-related documents continue to be debated, reviewed, and potentially released, the country stands at a crossroads. It can demand truth while respecting the presumption of innocence, or it can allow suspicion to become sentence. The difference will define not only how this case is remembered, but how future reckonings with power and abuse are handled.

The Epstein story is far from over. But if it is to end in justice rather than chaos, it will require something increasingly rare: patience, precision, and the courage to protect both victims and the innocent at the same time.